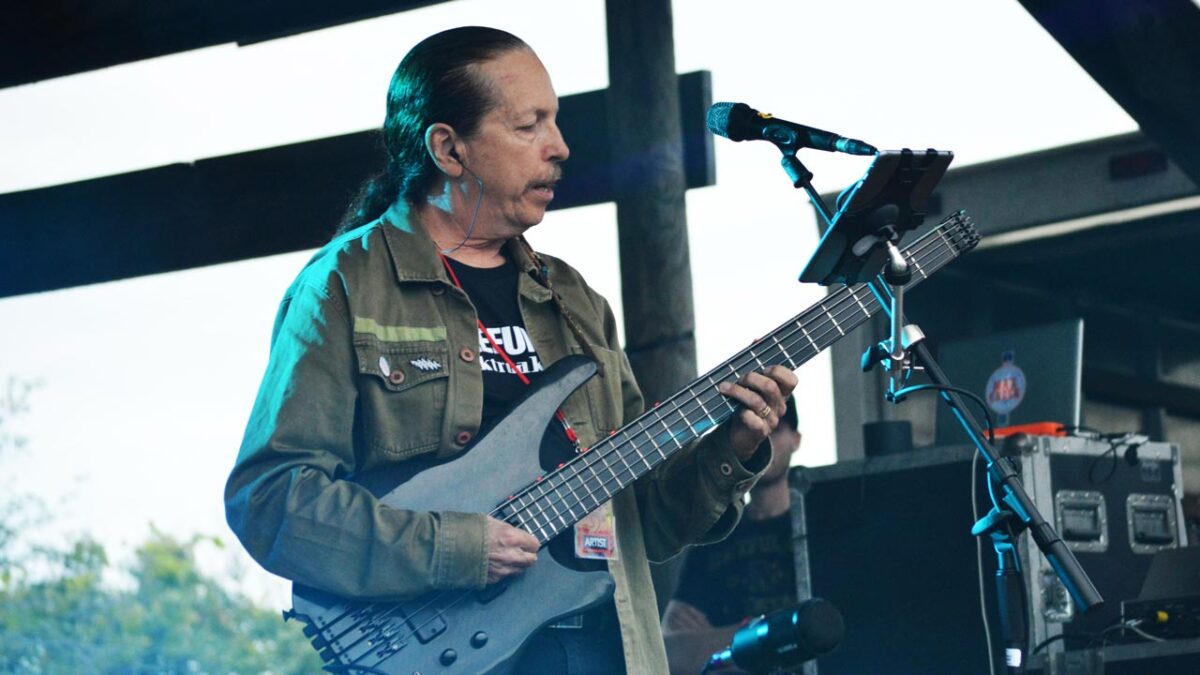

Episode 57 of Hooked on Creek features my interview with John Rider, founding member of Max Creek.

In this episode, John talks about the formation of Max Creek, his musical influences and his experiences performing, recording and writing music in the band. John also talks about growing up in Virginia, his bass guitars and the evolution of the jam band scene, among many other things.

This episode also features segments of the song Crystal Clear performed live by Max Creek at Broad Brook Opera House in Broad Brook, Connecticut, on April 20, 2024.

Transcript of episode 57

You’re listening to Hooked on Creek, a podcast celebrating the music, history and fans of the legendary jam band Max Creek. I am your host, Korre Johnson, and you are listening to episode 57.

Thank you for joining me on a very special episode of Hooked on Creek featuring my interview with John Rider, founding member of Max Creek.

In this episode, John takes us on a journey from his early days growing up in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains to the formation of Max Creek and 53 years of making music with the band. Along the way, John reflects on the influences that shaped him as a musician, the band’s evolving identity within the jam band scene and the special connection between Max Creek and its devoted fans. All that, and a lot more is packed into this episode, including his answers to questions submitted to me by his fans.

As a reminder, you can find links to the music featured in this episode in the show notes, and if you head over to hookedoncreek.com you can read a full transcript of my conversation with John. Alright, now let’s get started.

[interview begins]

Korre: John Rider, welcome to Hooked On Creek.

John: Happy to be here, finally.

Korre: Well, it means a lot to me, John, that you’ve taken the time to come on this podcast. I know a lot of fans of Max Creek have been asking me, “When is John going to be on the podcast?” And, I’ve had an opportunity to talk to all of the other current and former members of the band. So, it just means a lot to hear your voice on this podcast, John.

John: I’m a hard person to pin down sometimes, but we finally did it here.

Korre: Yeah. Well, to kick things off, I’m curious, when you’re up on stage in front of a crowd of Creek Freaks ready to start a show, what are you thinking about as you look out into that crowd?

John: It’s a lot of different things, but the main thing at first is getting my sound right. Even though we’ve had sound checks and things like that, I just in the first song to get the sound of the bass the way that I want it to be because I’m big on actually a certain type of sound that the bass should have. So, that’s the first thing I’m doing. And then, I’m usually looking out at the crowd itself, just picking out people that seem to have a lot of energy, which gives me energy. So that’s what I’m looking for in the first five minutes as such. And then, I think about my Uncle Weldon — no, I’m just kidding.

Korre: When you think back to your own childhood, what were some of those influences growing up that brought you into this appreciation of music? And maybe just talk about your childhood and what was that like for you?

John: Well, I grew up in the southwestern side of Virginia and the kind of rural farmland kind of in the mountains, the Blue Ridge Mountains. Max Creek is a creek, of course, that flows through a community, Max Creek, where a lot of my relatives settled and had been there for a couple hundred years I think. So growing up there, I spent a lot of time hiking, going swimming in the creek and also listening to bluegrass music, which was really big just across the border in North Carolina from there was the Galax Fiddlers Convention. I used to go to that every year when I was little. So, that influenced a lot of things that I was doing with music early on with Max Creek.

Korre: What were your parents doing? What was their livelihood? Did you have brothers and sisters?

John: Yeah, I had one sister, Kathy, and then my mother and father. My mother was a church secretary and my father, he was a colonel in the army and then he left that and he worked in pigments for paint and things like that. And he also worked in magnetic oxides, which is kind of a pigment that’s put on to acetate, and that’s what we use for recording tapes. Anyway, he later developed a process for putting that on tapes that was used in every major master tape in the world for audio recording and later for video recording, too. So he knew his oxides.

Korre: So where in this either family or community that you grew up did you find inspiration to yourself pick up music?

John: Well, my mother was a drummer in an orchestra. It was like an all-girl orchestra. We used to practice in the early days. We’d go out to lunch, we’d come back and she’d be down there on Bob [Gosselin]’s drum kit playing away. It was funny. And a big inspiration was my aunt who played violin in the Roanoke Symphony Orchestra in Roanoke, Virginia. She lived with my grandmother. They both really encouraged me to sing a lot. In fact, my grandmother was sure I was going to become a Vienna choir boy or something. She was always pushing me for that.

But I think that my Aunt Margaret, who played the violin, really inspired me. She was very good. So, I spent a lot of time when I was at their house playing on their piano that they had there. Also, her daughter was a concert pianist, so that also influenced what was going on with me. But aside from that, just aunts, uncles and everything back in the more backwoods kind of areas — had mandolins and banjos and that type of thing, and that kind of influenced where I was going early on, too.

Korre: When you think back to that time period, were you also aware of more popular that was happening on the radio?

John: Oh yeah. We’re talking ’50s here and Elvis Presley and all that. Yeah, I was definitely following that. My sister was older. I can remember with my parents dropping her off at an Elvis Presley concert in Roanoke, Virginia. But then by the time I was in junior high, I was really, really influenced by The Beatles, of course. Everyone who was 13, 14 years old in some way was influenced by The Beatles. I was influenced because I said, “Hey, that’s what I want to do.” And so I started a band way back then.

Korre: So you had a band when you were a teenager, is that right

John: Yeah, had a band when I was like 13.

Korre: What was it called?

John: That one was called The Key Three. It was kind of an acoustic thing, and then of course it was three people, so playing acoustic guitars and Kingston Trio-ish kind of thing. But then as The Beatles came along, I changed more to a band that was called Chords Incorporated because it went electric. That was a four piece: guitar, rhythm guitar, bass and drums. And at the time, I was playing “rhythm guitar,” if there is such a thing at this point in time. After that, the next band was called The Den of Thieves, and that was the last of my high school bands.

But then I went on to college at Hartt College of Music playing the trumpet. So, that’s the instrument that I graduated on. And probably in some of the folklore that’s gone on about Max Creek somebody has probably mentioned the fact that Dave Reed and I sat beside each other in the orchestra and band at Hartt College music. He played trumpet also.

The year we were graduating — we weren’t graduating — but we were actually just sitting in my room talking, and I think we had a couple of girls there we were trying to impress, but we were singing and playing guitars. And he said, “When we graduate, there’s probably going to be about 10, 15 positions for trumpet players open in the whole United States. Maybe we should do something else.” And I said, “Well, I always wanted to play bass, so I’ll buy a bass and I’ll play bass.” And he said, “Well, I play guitar and I’ve got that, so let’s start a band.”

He said, “I know a drummer.” And that was Bob Gosselin. That happened to be on my birthday. So, that’s why we sort of peg around the end of April as our anniversary of the band coming together. So there were. We became a band. At first the idea was to call it Red Eye, but we soon discovered that there was a national act. So, we changed it over to Max Creek which was the area in Virginia that I came from.

Korre: Was that a hard sell to get Dave Reed and Bob Gosselin to pick up the name Max Creek?

John: No, not really because it fit. At the time, it was a country-rock kind of band, and so Max Creek fit what we were doing. That soon changed and we became a little more psychedelic in what we were doing. I mean, we still always had the bluegrassy stuff. Even today we still have it going on and a little bit of country blend and Dylan stuff — but we’ve also discovered other things.

Korre: As you know, I’ve had an opportunity to talk with other band members. When I was talking to Mark Mercier, he told me that you were the first person or maybe one of the first people he met when he was at college. Can you tell me about what you remember about meeting Mark and that interaction you had with him?

John: Yeah. My parents were driving me to University of Hartford. We got in there and to get to the dorm area, there’s a bridge that you had to go across and we didn’t know where the dorm was. There wasn’t a map or anything for the one that we were looking for. And so there was this tall guy going across the bridge. So I said, “Pull over here.” And I leaned out the window and I said, “Hey, where’s Olmsted house?” And he says, “Oh, that’s where I live.” He said, “It’s up there, first building on the left.”

And so, OK. I go up, start unloading to get there, and then I discovered that it was Mark Mercer and he was my suitemate. We had four rooms around a living room in that area. And then by the next year, he became my roommate. So, that’s how I met him.

Korre: When I talked to Scott Murawski, he also was reflecting on meeting you. Scott told me about one of his first meetings with you. He said he was invited to a rehearsal, and he remembers seeing you show up in your Thunderbird with your long hair, sunglasses and headband. You must have had a reputation already at that time.

John: Yeah, that was my old T-Bird. Wish I had it now. At the time it was a 1959, and it wasn’t that old in 1971, 1972. It was just a junk car. I bought it for $176. But, it made a lot of noise. It had a 430 cubic edge engine in it, and I thought it was cool.

Korre: Well, at that time, I understand Scott was pretty young. I think he was 15 years old and you were probably what, 19 or 20

John: I was older than — oh, he was 15. Yeah, I was 21. Yeah, that’s right.

Korre: Do you remember those early rehearsals with Scott and what were they like?

John: Oh, yeah. I remember the first rehearsal. Dave Reed said, “I’ve been giving this kid some trumpet lessons, and I’ve been going over to his house, and he happened to have a guitar in the corner.” And he said, “Hey, can you play that thing?” And Scott picked it up and said, “Yeah, I can play some things.” And so Dave said, “Maybe you ought to come to rehearsal with us.”

So, Dave brought him over and said, “When we tell you to, you just play.” So, we would play along. Dave would nudge him and Scott would just start picking away. And we were all like, “Wow, that’s good.” So, even in the first gigs that we had him on, Scott was standing there because he didn’t really know the songs or he wasn’t singing at that point in time. But boy, when he just start playing the lead part, then he really shone at that point.

So, he was in the band and then he was out of the band because places that discovered that he wasn’t 20 or, well, he wasn’t 18 at that time, was the drinking age. So, he was out of the band for a while. And then after a few months, we decided we wanted him back in the band. So, we went back to these places and said, “Oh, he had a birthday. He’s 18 now.” So, we told everybody he was 18 and he was actually 16. But anyway, it worked. So, he was in for good at that point.

Korre: The album Max Creek came out in 1977. So, I would imagine you guys were thinking about this for a few years maybe, and you got to a point where you made it happen. How did you make it happen?

John: We were trying at some place to get in and get a record deal or this and that, and we finally decided that maybe it’s better that we just try to self-produce something. So, the first thing you had to do was find somebody with some money to bankroll the whole thing, which we did. Then we had to find a studio. So, we found this studio called The 19 that happened to be number 19 on the street that it was on. Anyway, we went in there and developed a good relationship with those guys, and we made a couple albums with them.

We had to start our own record company called Wranger Records. It was an interesting learning curve at that time, learning how you actually made records and how you had to get the guy to master it that knew exactly the heat of the needle that was going to cut the record and then press it into vinyl. So, there were people around that could do this really well, and people that didn’t do it so well. We finally found someone in Texas — was the guy who always cut all of our vinyl.

Korre: At that time, Amy [Fazzano] was in the band and I don’t think it was too long after that Rob Fried joined the band. And then in the 1980s there were I think — at least from what I look online — a lot of shows, a pretty heavy schedule of being out and about at clubs and playing music. Talk about the early and mid ’80s for Max Creek and what that experience was like.

John: We had tried some different people as acting as agents with us, but we got with an agency called Flash Groups. They were out of New London, and they were able to book us just about anywhere we wanted to go. So, we started branching out from the Connecticut area over to the Providence area playing at Lupo’s — which at that time it was a big road trip for us to go to Providence, so we had to rent hotel rooms. Now if it’s two hours away, we’d just drive back. It’s not that type of thing. But at that point, that was the big road trip.

But then soon Flash Groups got us moving around all over New England and out to Rochester, Syracuse, down to Virginia, Georgia, and that type of thing. So, I think during one of those years, like 1983, I think we played 252 times that year, so that was a lot of playing. I think we went playing for, at that time, seven years straight without ever taking a week off.

Korre: Wow. Were you ever thinking that you were going to be a rock star? Were you chasing that fame that you might’ve seen from others? Where was your head at?

John: Of course. Yeah, definitely. I thought I was going to be rich and retire by the time I was 40. That was in my head. The Beatles did it. Why not me? But if that were the only thing that was driving us, we probably would’ve quit after 10 years. It’s other things that I think that have kept us together and going, and the energy from the crowd and from friends that we’ve made that have lasted for half a lifetime here. So yes, I wanted to be a rock star, but there’s more to what has gone on with Max Creek than that situation.

Korre: When I look back at that time period — or maybe into the late ’80s or early ’90s — as a fan of music, we saw bands like Phish and Widespread Panic and some of these other bands that sort of popularized this genre of music, and there was a period in the early ’90s when that was becoming a little bit more mainstream. Can you remember where your head was at or where Max Creek was at as sort of that scene was unfolding and how you guys navigated it?

John: Well, we were kind of going along on the same areas in the same places, like the Boulder Theater, that Phish was playing. We were doing that, and we were getting to the point that we were selling quite well on these other markets that Phish was selling. And suddenly we had a name — people were always asking us in the ’70s and ’80s, “Well, what kind of music is it you play?” And it’s like, “Well, I don’t know. It’s just a lot of different things, jazz and folk and this and that.”

And then suddenly it became in the early ’90s that this was jam band music. OK, alright, here’s our name. “What are you playing?” Now I can say, “Oh, we play jam band music,” and everyone knows what I’m talking about. But for a number of years, like 20 years at least, we couldn’t put a name on it, really. And so the ’90s brought about the jam band music, and we played it with a number of jam bands like Widespread Panic. We would go down to Georgia and play with them. They’d come up here and play with us. So, at least we finally got a name.

Korre: Well, I’m kind of curious, if you look back now as a musician who was playing so much and having the opportunity to meet other musicians, who was inspiring as you were out there with Max Creek? What other bands or what other bass players or musicians did you look to as inspiration?

John: Well, the first bass player that really inspired me with Jack Casady with the Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna — especially his playing with that — that inspired me. Then later, but not much later, when a friend of mine — actually, he was a guy in my college fraternity — said, “You got to come down to Dillon Stadium and see this band called the Grateful Dead. I got two extra tickets here.” I looked at the ticket, it said $4.50. It’s like, “Eh, I don’t know if I want to go or not,” but I did. He said, “You really got to go because there’s a lot of songs that they’re playing that are the same songs that you’re playing, but they play it a little differently in this.”

And it was. It was I Know You Rider, it was Going Down the Road Feeling Bad and things — and we played it differently. So, it was kind like I was there and my mouth was kind of open like, “Wow.” And this was a time that is was on a football field and you could just walk to the front through the crowd with everybody dancing and walk around to the side. And I mean, it wasn’t just a press of people, it was just a gathering of people. So, it was great. And I said to myself, I says, “Yeah, I want to be a part of this, too.”

Korre: Well, when I think of the Grateful Dead and I think of Max Creek, there are obviously some similarities. One of the most striking ones to me — now that I’ve gotten to know your band, John, and your music and the community — is just this sense of identity that the fans have with this music. When you’re a fan of the Grateful Dead, you are a deadhead. It can feel like a lifestyle. It can feel like a club or community of people who are all sort of in the know of a thing. And I have that feeling with Max Creek, and I’m curious how you think about it from your perspective.

John: That’s the way I think about it. When we started the whole thing — I’m kind of joking around about The Beatles, and yes, I want to do that and everything. But when Dave and I and Bob were talking about it early on, we wanted to provide a place for all kinds of artists to do whatever it was that they were doing, making posters, flyers, people who were doing paintings — a lot of our early album covers, a person was working on that, Linda — and also to provide a place for all these people to come to that had like-minded processes going on.

So, I hope that that’s what we are continuing to do, but that was the original thought that it would be this group of people that would all be artists, writers, and now people who are doing podcasts and all contributing to the whole thing.

Korre: In addition to being a performer on stage, John, you are writing songs. I’m curious, when you reflect back on that period of your life, did you have something to say? Were you looking to say something and was this music away for you to get your thoughts out there? How would you describe your writing or what inspired your writing?

John: Oh, yeah. They’re all involved with life events and possibly people. Some of the songs are about several people within the same song. Back in time when you’re younger and everything, there’s more angst going on and more loves being lost and this and that, you write a lot more. Because now when I write, I am analyzing and thinking more about it and that type of thing, whereas then it’s like, I have to get this down. I have to get this on paper. We have to get it out. And that’s kind of the way it worked at that point in time.

Now, I sort of just, I’m writing words and I’ve got one-liners. I probably have 200 one-liners and t’s like, “Boy, each one of these is great”, but it’s not going anywhere.

Korre: I think I can speak on behalf of all of your fans that we’re eager to see some of those one-liners make it on stage, John.

John: Hopefully they will. And now my son Clayton is out there writing, so maybe one or two of his songs will make it up on stage with us. But he’s played with us a couple of times and he’s a very good guitar player, and he sings much better than I do.

Korre: What are some of your favorite songs to play now? I mean, when you lock in on a song, or when you think about a set list, do you find yourself really into certain songs nowadays versus earlier on? Or how do you approach that?

John: I don’t know. Sometimes you get stuck on ones that have elicited a greater crowd response, and then all of a sudden it’s like you look at the lists that people make up of what happened. You say, “Oh, boy, I’m just playing that crazy.” Or someone says to me, “You’ve been playing that song an awful lot.” It’s like, oh, OK. And it’s basically, “Yeah, well, I like that song.”

But you have to mix it up. I mean, every time I’m playing and I’m playing a song, sometimes it’s one of Scott’s songs, one of Mark’s songs that I just get in my head, and even after we’ve played it, I’ll wake up in the morning, I’m hearing that song in my head, too. And they change over time. They’re not exactly the same.

And even within our own shows, one show to the next show, a Just a Rose might not be the same at all. It’s just a totally different feel to it. So, I don’t know. And that’s what I enjoy about Max Creek is things change. We’re not just here’s my set from the beginning to end with thousands of lights and set changes, and there you go, but you go to the next show and it’s the same thing again.

Korre: Well, there are probably a lot of secret ingredients to Max Creek, but I think that’s one of them — this feeling that things change and there’s a sense of unexpectedness that comes to a show, and that’s what makes it fun, right?

John: Yeah. Oh yeah. That would be what made it boring if it didn’t happen.

Korre: Well, John, I have a handful of questions that your fans wanted me to ask you. So, I’m going to run through a few of these and let me know what you think.

John: OK.

Korre: Mark Madigan asked, does John’s early background as a music educator inform his approach to performance? And does John’s love of audience sing-alongs have any relation to his work as a middle school music teacher in the ’70s?

John: And Mark Madigan just happens to be one of my former students, so that’s why he said that. And he’s actually a professor now in college in Rochester. But yeah, he would ask that. And yes, definitely I like the sing-along kind of thing and I used to do that with my classes. I would bring my ancient 12 string guitar in and I would play along and do the call and response kind of things with the kids to get them involved with what was going on.

And I also did special ed classes that way, too, because those classes liked that kind of call and response thing where I’d say the first words and then they repeat it. Those are some of my favorite classes actually that I had. But yes, Mark Madigan, I took all that, everything that all you guys did to me in that school and I put it to work.

Korre: Daniel Bowser asked, why doesn’t John play his song The Seven more often? It’s one of his best songs.

John: Well, I play it every year at New Year’s, that’s traditional. And then every once in a while we will pull it out. You know, I don’t have a good answer for that. I think part of it is it’s like this sacredness of what that is — that song is to me — that it’s just, I can’t overplay it, but I like it every time I play it.

Korre: Well, that song is, for me as a listener, it is this feeling, it’s almost cryptic. It has this prog-rock feel to it and I listen to that song and I just think about it.

John: Well, that’s exactly what I hope happens with every song that I write. People ask me or they say to me, “This is what you were thinking when you wrote that song.” And I say, “Yeah, you’re right. That’s exactly what I was thinking.” Because I think that songs should have different meanings to different people. You haven’t had the same life experience that I’ve had, but you hear the words and it means something to you, maybe — and not necessarily the exact thought that I had when I was writing it. But, I think everyone’s perception of it is legitimate.

Korre: Bob Honch said, I’d like to know about all the basses that John has used over the years and what are his favorites. So maybe you can talk about your bass guitar and maybe how that’s changed over the years.

John: The first bass that I had where they said, “Let’s go out and buy a bass and started playing it,” was a Beatle bass, the Hofner. In fact, I’m turning around and I’m looking at it right now — shaped like a violin that Paul McCartney used. But I didn’t use that for long because It had a certain tonality. So, then I went to a Fender Precision bass. And that one I still have, and it has a certain sound. I really don’t play it that much, but I like it.

After that, I went through a bunch of other basses, and it seems like after I’d play them for a month or so, I’d sell them to Scott. It seems like Scott has a couple of my basses that I just didn’t like. And then while I was still teaching school, I had access to the shop at school. The shop teacher was a good friend of mine, so I actually built a bass in the shop.

It was a four string bass that had a separate pickup for each string, and these pickups would slide along a metal plate, so you could change the tonality by sliding the pickup to a different area. And then inside of the bass, it had four preamplifiers and four outputs. So, each one of the strings went to a separate equalizer so the tone could be changed there on each string separately, and also a separate preamp on each one of those.

And they happened to be four separate tube preamps, then to the equalizer, then out of equalizer it went into a mixer where you could send the sound of each string to a different speaker-amp combination. So, you could have sort of a string across the stage kind of deal. So, it was one of my weirder times, but I had four amps and four speakers.

Korre: Did Phil Lesh do something like that? I remember watching a documentary about the Grateful Dead and I think there was something like that with his, right?

John: Yes, he did. But that was when they had the Wall of Sound thing going on. He had something very similar to that situation, along with we had the Wall of Sound situation where we had the double microphones and we had the PA behind us, also. But it was very small compared to theirs. Anyway, we had fun. I digress But, I ended up going to a Spector bass. The guy that had designed this particular specter bass worked for Steinberger. So, he actually quit Steinberger and started Spector and started making these basses that were kind of odd shape.

So anyway, it sort of looked kind of like an arrow, this particular bass. Anyway, then I got rid of that, and 20 years ago I got the bass that I have now, which is the Status bass, which this particular bass was made famous by the Who, the bass player, John Entwistle. Yeah. So, John Entwistle had this particular bass. The reason why I got it was because my shoulder was hurting from carrying that 18-pound 4-pickup bass for so many years that I needed something lighter, and this thing only weighs 5 pounds because it’s made out of Kevlar.

So, I’ve loved the sound of this particular bass for the last 20 years. That’s what I stayed with. Got a few cracks and a few chips in it, but it’s still playing.

Korre: This next one is from Bill Hoy. Bill Hoy said, ask John what he has for tapes and recordings. Does he keep an archive of the band’s history?

John: Oh, yeah. Yeah. I have all the original test pressings for all the vinyl and things like that. There is one set of master tapes that got lost somewhere, and I’m not going to say which because we were able to remaster it anyway without that master tape.

Korre: Well, if there’s anything that you want to release from the vault, I’m sure your fans would be eager to hear it.

John: I think you interviewed Fred Moore, didn’t you?

Korre: Yep. Fred. Yeah.

John: So, I’m actually looking for some tapes for Fred. People had gone through my tapes and they had made another set of tapes on DAT tapes to be used on a compilation of Creek through the ages kind of things. So, he says that I must have those master tapes, and I’m like, “Well, I don’t know.” So, I’m still looking for them, but I think he’s probably right. I probably do have them. You know those little DAT tapes, they’re so easy to hide. The two-inch master tapes, they’re easy to find.

Korre: I’ll change it up for you a bit. Beatrice Fabian asked, what are the tricks John uses to keep his wonderful relationship with Sally [Rider] vibrant and exciting?

John: Those tricks? Yeah. Well, Sally is just a great person, and she is behind me 100 percent in whatever we want to do. And we have remade ourselves also — changed with whatever is going along. We also own a production company that produces concerts or corporate meetings — large corporate meetings like down at Mohegan Sun. All of my boys work for us, so I have got three sons that are in that business.

Korre: This is Rider Productions, right?

John: Yeah. But we also have a travel business. It’s corporate travel or personal travel that is actually doing quite well at the moment. All of a sudden after the Covid gave up, people started wanting to travel. So, there we go.

Korre: What is it like to have your family in your business? I mean, that must be incredibly rewarding to be working with your family in that.

John: Yeah, and fortunately I have three boys who are very easygoing and easy to work with. I mean slowly but surely within the production end of things, they are taking over. So, the last show that we did a couple of weeks ago, I pretty much didn’t do anything other than supervise that everything got put together the right way and that type of thing. One of them runs sound, one of them is doing the video production part of it, and the other one’s doing the lighting. So, it’s a good thing.

It’s nice to have your family. When I talk to so many families, like their kids went as far away from their hometown as they could possibly get. So, it’s nice that my boys chose to stay around.

Korre: When you look back at the last 50-plus years, are there any specific venues that stand out to you as places that you’re really fond of or that you have really strong memories about the performance or the night?

John: Yeah. I loved the place that’s no longer there in Harvard Square called Jonathan Swift’s. We loved playing there. It was kind of down in a basement like you were in a cavern or something, but it was nice. And we played with a number of people. Jorma [Kaukonen] played with us there a few times, and we had a very good relationship with him. And another place, of course was Lupo’s. And The Living Room, where we played every Wednesday night for seven years — and that kind of built our Rhode Island following, that Wednesday night deal for all those years.

Then of course, Camp Creeks that we have done. I always viewed those as one of the pinnacles of our whole thing of getting people together and having people have a good time and camping and nobody had to drive home after the show and that kind of deal. So, I always enjoyed the Camp Creeks.

Korre: Are you ready to announce a 2025 Camp Creek yet or are we not ready for that?

John: I’m always ready to announce, if it gets to that point. The Camp Creeks, they’re hard to put on. They’re very expensive to put on. And once again, it’s like putting out an album. You got to have the funding behind you to do it. And slowly, there may be some funding coming in here, so we’ll see where it goes.

Korre: When you look back, do you have any regrets? Anything that you wish would’ve went differently or thought could have went a different way?

John: Not really. Yeah, I wish we had made this kind of money like Taylor Swift. But then again, we wouldn’t have the kind of band that we have. It wouldn’t be the same. We’ve had a lot of friends along the way who are no longer with us at this point, but nevertheless, those friendships were really solid. Somebody asked Kamala Harris the same question and they think that her answer ruined her career. She said, “No, I wouldn’t have done anything any differently.” As I was saying, I was thinking, “Wait a minute, this didn’t turn out well for that person.”

Korre: Well, let me flip the question around. What does the future hold for Max Creek?

John: When somebody had asked me that when we were at our 10-year anniversary show, I would’ve said, “Well, we’ll probably just stay together a couple more years and that’ll be it.” And then the same question was asked at the 25th anniversary show and, “We got a few more years.” So, at this point at 53 years, “We got a few more years, so I guess we’ll just keep going.” I see no reason to change the way we’re doing anything at this point. As I said, we keep changing things around and changing things up such that everything is different every time we play. So, I’m not bored with it, so hopefully other people aren’t.

Korre: John, I’m near the end here and I want to make sure that you have an opportunity to say anything that I might’ve missed.

John: I don’t know. As I said, there are some friends that along the way, like Rick Danko, who was a big influence on just how I looked at things in the band world. And Phil Lesh. Phil Lesh, he was good to me on a number of occasions, invited me up on stage to talk about basses and bass sounds at different points in time — but that’s probably another story for another time.

Korre: Well, John Rider, I had a lot of fun talking with you today.

John: Oh, you know what? I wanted to ask you a question. What possessed you to start doing this project that you’re doing here?

Korre: So, I live in Milwaukee, and I have a friend of mine who is really into Phish, and I really enjoy Phish, as well. Mike Gordon was in Milwaukee on tour, and I was not really familiar with his band, but I knew I liked his music. And so I went to a Mike Gordon show in Milwaukee, and I found myself as much captivated by this guitar player. I had no idea who Scott Murawski was. Never heard of him. Never heard of Max Creek ever.

I left that show, and the first thing I did when I got home, John, was Google, who is in Mike Gordon’s band? And then I’m like, who’s Scott Murawski? And then the first thing I saw when I did this was a series of YouTube videos in black and white at some farm in 1982 or something. And I saw you as a young man and this band I’d never heard of playing these songs.

And first, I was confused, honestly. I was like, what is going on here? This is so cool. And it was so interesting to see this old footage of it. And then I did one more thing, and this sealed the deal for me. I looked a little further and I saw all of the live music from Max Creek posted online. So it gave me an immediate next step. Like, well if you have questions, here are your answers. And so I started listening to the stuff, and then I just kept listening over and over for weeks and weeks.

And then I did a Google search, and I found it was probably a Facebook community for Max Creek and some other things. I’m like, there’s a whole scene here of people and a whole world that I’m not even aware of. And I got so fixated on trying to understand what it is and what it was because I loved the music so much. But the problem is I’m in Milwaukee and I have nobody around me who’s ever heard of this band.

And so I created the podcast as a way for me to have an outlet to talk about you and Max Creek and this music, because I had nobody else to speak to. And so I’m sitting in my basement, like I have been for the last five and a half years, talking to myself about this band, but connecting with these fans across the northeast and now across the country, really, who love Max Creek. And this podcast gave me a way to do that that I wouldn’t have found locally in Milwaukee. And so, it’s been so rewarding for me.

John: That means that what I had wanted to happen 53 years ago has happened for you. So, that’s very meaningful for me.

Korre: Well, I will see you in January at The Met. I’m flying out. I’m really excited to see you guys. And again, just thank you so much for joining me on the podcast.

John: Well, thanks for having me on, and as I said, I enjoyed myself, too.

[interview ends]

And that concludes episode 57 of Hooked on Creek. It was an honor getting the opportunity to talk with John Rider on this podcast. I am grateful for the time he spent with me and I hope you enjoyed our conversation.

If you are curious, this episode featured clips of Max Creek performing their song Crystal Clear performed live at Broad Brook Opera House in Broad Brook, Connecticut, on April 20, 2024.

If you have feedback about this episode or suggestions for future episodes of Hooked on Creek, please visit hookedoncreek.com and click the contact link to send me a message. I would love to hear from you. Thanks for tuning in!